As Teen Use of Weight-Loss Drugs Rises, the U.S. Childhood Obesity Debate Enters a New Era

GLP-1 medications are moving from adult clinics into pediatric care. Supporters call it overdue treatment for a chronic disease; critics worry about long-term safety, cost, and what it means to “medicalize” childhood.

A quiet surge in teen prescriptions

A few years ago, weight-loss injections for teenagers were rare enough to be a curiosity. Now they are becoming a recognizable, if still small, part of pediatric obesity care. Reuters reported that use of Novo Nordisk’s Wegovy (semaglutide) among U.S. teens rose sharply, citing health data that showed prescription rates increasing from 9.9 per 100,000 teens in 2023 to 14.8 per 100,000 in 2024, and 17.3 per 100,000 in early 2025. Even after that jump, it remains a sliver of the population compared with the large share of adolescents living with obesity.

The acceleration is not limited to one brand. Research tracking GLP-1 dispensing in adolescents and young adults shows a steep upswing from 2020 through 2023, coinciding with blockbuster adult demand, broader awareness among clinicians, and new pediatric indications.

What changed is not only the drugs, but the medical posture. In 2023, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) issued a major clinical practice guideline that treats obesity as a chronic disease and supports more intensive interventions, including pharmacotherapy for adolescents 12 and older with obesity when appropriate.

Are U.S. kids getting more obese? The long arc says yes

Before weighing whether teen medications are “a good thing,” it helps to start with the uncomfortable baseline: childhood obesity in the United States is not new, but it has grown dramatically over time and remains historically high.

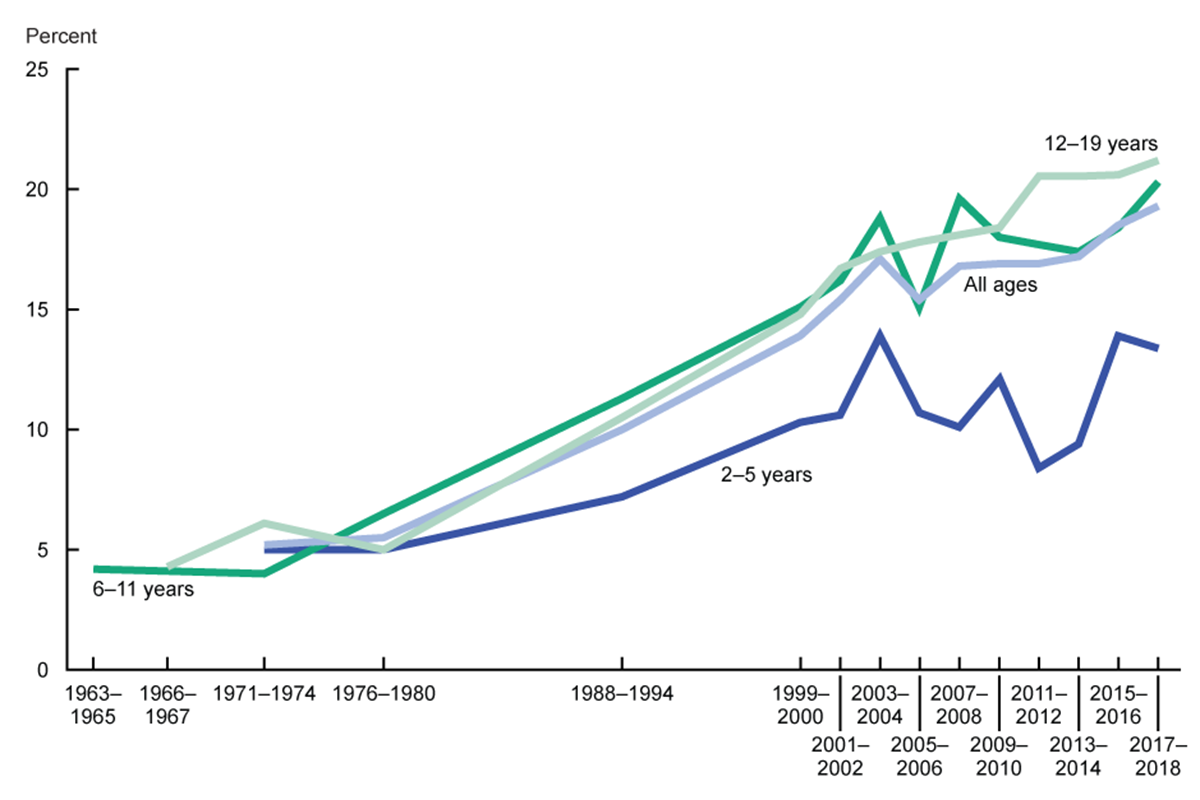

CDC survey data using measured height and weight show that the share of U.S. children and adolescents (ages 2–19) with obesity rose from about 5% in the early 1970s to roughly 19% by 2017–2018. Severe obesity increased as well.

Using a slightly different time window, the CDC reports that from 2017 to March 2020, the prevalence of obesity among U.S. youth ages 2–19 was 19.7% (about 14.7 million young people).

Child obesity in the US – Graph. Child obesity is Body Mass Index at or above the 95th percentile from the CDC Growth Charts.

Chart 1: Childhood obesity over time (U.S. ages 2–19)

| Survey period | Obesity prevalence (%) | Severe obesity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1971–1974 | 5.2 | 1.0 |

| 1976–1980 | 5.5 | 1.3 |

| 1988–1994 | 10.0 | 2.6 |

| 1999–2000 | 13.9 | 3.6 |

| 2003–2004 | 17.1 | 5.1 |

| 2009–2010 | 16.9 | 5.6 |

| 2015–2016 | 18.5 | 5.6 |

| 2017–2018 | 19.3 | 6.1 |

1971–74 5.2% ███ 1976–80 5.5% ███ 1988–94 10.0% ██████ 1999–00 13.9% █████████ 2003–04 17.1% ████████████ 2009–10 16.9% ████████████ 2015–16 18.5% █████████████ 2017–18 19.3% ██████████████

Notes: Obesity is BMI at or above the 95th percentile for age and sex; severe obesity is BMI at or above 120% of the 95th percentile.

What the pandemic did: a shock to routines, a stress test for systems

Even before GLP-1 drugs became household words, the pandemic years highlighted how quickly weight trajectories can shift when daily life is disrupted. Multiple analyses describe rapid excess weight gain among U.S. youth during early COVID-19, with school closures, reduced structured activity, and changes in sleep and eating patterns as likely contributors.

For clinicians who treat pediatric obesity, this matters because it reframes the timeline. If weight can change quickly during disruptions, then “watch and wait” can look less like caution and more like missed time—especially for children already trending toward severe obesity, where risks to cardiometabolic health rise sharply.

Why teen medications are rising now

The increase in prescribing is not simply cultural hype. It tracks a series of concrete policy and regulatory shifts:

- New pediatric approvals. The FDA expanded or approved several anti-obesity options for adolescents in recent years, including Qsymia (phentermine/topiramate) in 2022 for ages 12 and older, and Wegovy (semaglutide) for ages 12 and older.

- A clinical green light. The AAP’s 2023 guideline supported earlier and more intensive treatment, including pharmacotherapy for adolescents 12 and older with obesity when indicated.

- Better efficacy than older drugs. GLP-1 medications have shown strong weight-loss effects in trials and have reshaped adult obesity care, creating pressure to extend similar tools to teens with severe disease burdens.

In CDC reporting on adolescent obesity medication prescriptions, 2023 stands out as an inflection point: prescriptions rose substantially compared with earlier years, a pattern the authors link to new approvals and the publication of the AAP guideline.

Chart 2: Wegovy prescribing rates among teens (reported trend)

| Year | Prescriptions per 100,000 teens |

|---|---|

| 2023 | 9.9 |

| 2024 | 14.8 |

| Early 2025 | 17.3 |

2023 9.9 ████████ 2024 14.8 █████████████ Early 2025 17.3 ███████████████

Context: Reuters noted this remains small relative to the much larger share of teens living with obesity.

The case for GLP-1 drugs in teens: a chronic disease, not a character flaw

Supporters of teen pharmacotherapy make a blunt argument: the country has tried to solve childhood obesity largely through advice, stigma, and sporadic lifestyle programs—and the historical trend line has not reversed.

For adolescents with severe obesity, the stakes are not cosmetic. Obesity in youth is associated with higher risks of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, fatty liver disease, sleep apnea, orthopedic problems, and mental health strain. When clinicians call obesity a “chronic disease,” they are also pointing to persistence: a teen with severe obesity is statistically more likely to become an adult with obesity, with compounding risks over decades.

From that perspective, GLP-1 drugs are framed as a therapeutic correction—helping regulate appetite, satiety, and metabolic signaling in ways that lifestyle counseling alone often cannot. The AAP guideline, notably, does not position medication as a replacement for nutrition and activity. It frames it as an additional tool, ideally paired with structured behavioral and family-based support.

The case against: long-term unknowns, access barriers, and the fear of a shortcut culture

Even among clinicians who see real benefits, caution runs alongside optimism. Reuters captured a split: some doctors report meaningful improvements in teens’ health and well-being; others worry that pediatric use is outpacing the evidence base for lifelong outcomes.

Several concerns dominate the debate:

- Long-term safety in growing bodies. GLP-1 drugs are often intended for chronic use. What decades of exposure mean for adolescents—across growth, bone health, reproductive development, and mental health—remains an active research question.

- Side effects and monitoring burden. These medications can cause gastrointestinal effects and require careful follow-up. The FDA labeling also includes important warnings and contraindications that clinicians must screen for.

- Cost and insurance inequality. Access can hinge on insurance coverage, prior authorizations, and family resources. When availability is constrained, the risk is a two-tier system: affluent families get medications and multidisciplinary care; lower-income families get waitlists and lectures.

- What happens when the drug stops? Many patients regain weight after discontinuation, raising the question of whether society is prepared to support long-term treatment for large numbers of people—financially and ethically.

There is also a cultural critique that cannot be dismissed: if a medication becomes the headline solution, prevention efforts—food environment, marketing to children, school activity, sleep, neighborhood safety, and family supports—can fade into the background because they are harder, slower, and politically inconvenient.

So… are weight-loss drugs for teens a good thing?

The most honest answer is: they can be both a breakthrough and a warning, depending on how they are used.

They look like a breakthrough when they reach adolescents with severe obesity who have tried structured interventions, who are experiencing medical complications, and who can be monitored by clinicians trained in pediatric obesity medicine. In that setting, medication can reduce health risks and—just as importantly—reduce suffering. For some teenagers, weight is not an abstract statistic; it is pain when walking up stairs, bullying at school, and a sense of inevitability about health.

They look like a warning when they are treated as a mass substitute for prevention, or as a “reset button” that society uses to avoid confronting upstream drivers of childhood obesity. The United States did not arrive at nearly 1 in 5 children with obesity because kids suddenly lost willpower in the 1990s. The rise tracks broad changes: food availability and marketing, ultra-processed diets, reduced daily movement, screen time, sleep disruption, and socioeconomic stress—forces that medication cannot fully neutralize.

In other words, GLP-1 drugs may be best understood as a powerful downstream tool—one that can reduce harm for individuals—while the upstream work of prevention still determines whether future cohorts of children face the same risk.

What a responsible “GLP-1 era” could look like

If teen use is rising—and the data suggest it is—then the question shifts from whether prescribing should exist to what guardrails should define it.

- Clear eligibility and strong follow-up. Align prescribing with evidence-based pediatric guidelines and ensure monitoring for side effects, nutrition adequacy, and mental health support.